Acoustics

Acoustics

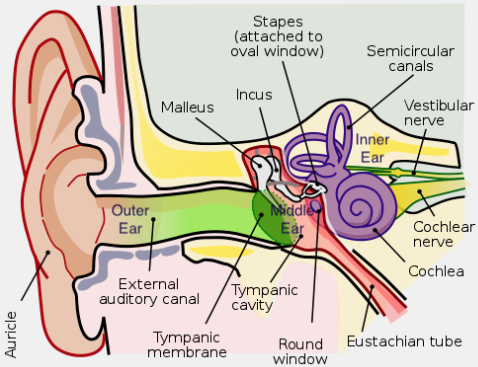

waveform, phase, amplitude (usually expressed in log units known as decibels, abbreviated dB), and frequency.

For human listeners, the amplitude and frequency of a sound pressure change at the ear roughly correspond to loudness and pitch, respectively.

Humans can detect sounds in a frequency range from about 20 Hz to 20

kHz. Most small mammals are sensitive to very high frequencies, but not to low frequencies.

|

|---|

| © Lars Chittka; Axel Brockmann |

Fragile X Syndrome (FXS) - Sensory Processing Deficits

-

Introduction

- Definition: FXS is a neurodevelopmental disorder leading to intellectual disability.

- Link to Autism: Leading known genetic cause of autism.

-

Sensory Processing in FXS

- General Characteristics: Abnormal sensory processing, particularly sensory hypersensitivity.

- Manifestations:

- Auditory, tactile, or visual defensiveness or avoidance.

- Clinical and behavioral studies show auditory hypersensitivity, impaired habituation to repeated sounds, and reduced auditory attention.

- Visuospatial Impairments: Significant deficits observed.

- Noted problems in processing texture-defined motion stimuli, temporal flicker, perceiving ordinal numerical sequences, and maintaining dynamic object identity during occlusion.

-

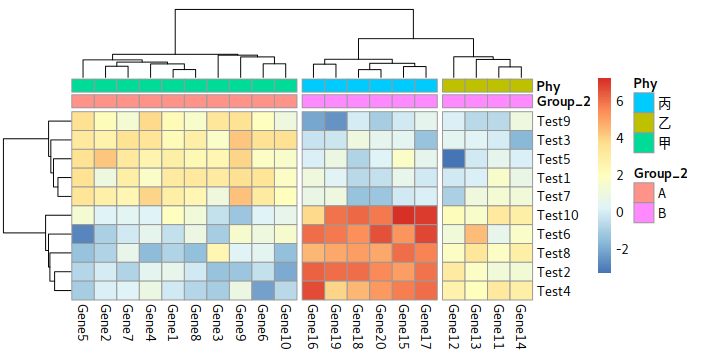

Animal Models: Fmr1 KO Rodents

- General: Fragile X mental retardation 1 (Fmr1) gene knockout (KO) rodents used as FXS models.

- Findings:

- Seizures.

- Abnormal visual-evoked responses.

- Auditory hypersensitivity.

- Altered acoustic startle responses.

- Abnormal processing in the auditory system.

- Tactile Symptoms:

- Individuals with FXS show tactile defensiveness.

- Fmr1 KO mice have impaired tactile stimulation frequency encoding and larger receptive fields in the somatosensory cortex.

-

Review Focus:

- Discusses clinical, functional, and structural studies on sensory processing deficits in FXS across:

- Auditory. (We only focus on Auditory in this note)

- Visual.

- Somatosensory domains.

- Discusses clinical, functional, and structural studies on sensory processing deficits in FXS across:

-

Significance of Animal Models:

- Observations in FXS humans and Fmr1 KO rodents are similar, suggesting conservation of basic sensory processing circuits across species.

- Offers a translational platform to develop biomarkers and understand underlying mechanisms.

-

Conclusion:

- Emphasizes the value of pre-clinical studies in animal models of FXS.

- Belief: Understanding mechanisms in basic sensory processing circuits/behaviors can boost the search for new therapeutic approaches in FXS.

Introduction

-

Prevalence and Impact: intellectual disability, Link to Autism: One of the leading genetic causes.

- Statistics: Affects 1 in 4,000 boys and 1 in 8,000 girls.

-

Genetic Origin:

- Gene Impacted: Fragile X mental retardation 1 (FMR1) gene.

- Causes:

- Silencing, Deletion, Loss-of-function mutation.

- Consequences: Results in the non-expression or nonfunctionality of the fragile X mental retardation protein (FMRP).

- About FMRP:

- Type: A messenger RNA (mRNA)-binding protein.

- Functions:

- Regulates several aspects of mRNA metabolism, including:

- Nuclear export.

- Transport to synaptic terminals.

- Activity-dependent ribosome stalling.

- Protein translation.

- Regulates several aspects of mRNA metabolism, including:

FMRP’s Role in Synaptic Function and Translation Regulation

-

Translation Regulation:

- FMRP regulates the translation of mRNAs at synapses.

- Some of these mRNAs encode proteins linked to synaptic plasticity.

-

Impact of Absence of FMRP:

- Results in dysregulation of protein translation and increased protein synthesis.

- This may contribute to altered signaling of metabotropic glutamate receptor 5 (mGluR5).

- This altered signaling may lead to exaggerated long-term depression (LTD) in the hippocampus.

-

Matrix Metalloproteinase-9 (MMP-9):

- FMRP negatively regulates MMP-9 translation in neurons because MMP-9 levels are elevated in FXS.

- mGluR5 and MMP-9 potentially mediate changes in synaptic functions.

- They might signal through the phosphatidylinositol-3-kinase (PI3K)/mammalian target of rapamycin complex 1 (mTORC1) and extracellular signal-regulated kinase pathways to amplify cap-dependent translation.

-

Recent Data on FMRP:

- Suggests that FMRP might directly regulate PI3K and mTORC1 signaling.

- This regulation could occur through other signaling proteins like phosphatidylinositol-3-kinase enhancer, phosphatase and tensin homolog, neurofibromin 1, and tuberous sclerosis 2.

- Suggests that FMRP might directly regulate PI3K and mTORC1 signaling.

-

FMRP Targets:

- All three isoforms of eukaryotic translation initiation factor 4 G.

- Eukaryotic translation elongation factor 1 and 2.

- Argonaute proteins.

- Dicer.

- Dysregulation of these targets might contribute to enhanced neuronal translation in FXS.

Role of Dysregulated Pathways and FMRP in Dendritic Spine Morphology and Neurophysiology

-

Dysregulated Pathways in FXS:

- Dysregulated PI3K/mTOR signaling.

- Enhanced mGluR5-dependent LTD.

- Increased MMP-9 activity.

- Reduced activity of the voltage and $Ca^{2+}$ activated ( K^+ ) (BKCa or BK) channel.

- These might contribute to the immature dendritic spine morphology in rodent models of FXS.

-

FMRP’s Role in Mice:

- Might regulate neuronal branching.

- Regulates dendritic spine development.

-

Clinical Studies in Humans:

- Alterations observed in dendritic spine number and morphology in the cortex of FXS humans.

- A notable prevalence of immature dendritic spines.

- Dendritic abnormalities are consistent anatomical features linked with intellectual disability.

- Alterations observed in dendritic spine number and morphology in the cortex of FXS humans.

-

FMRP’s Predominant Activity:

- Mainly related to the regulation of synaptic functions.

- Yet, there’s limited knowledge about:

- How synaptic alterations due to the absence of FMRP lead to neurophysiological and behavioral deficits in humans with FXS.

- The reason why abnormal dendritic spine development alone doesn’t explain the increased cortical excitability seen in FXS.

Using auditory reaction time to measure loudness growth in rats

Abstract

-

Introduction:

- Auditory Reaction Time (RT): Established as a reliable proxy for loudness perception in humans.

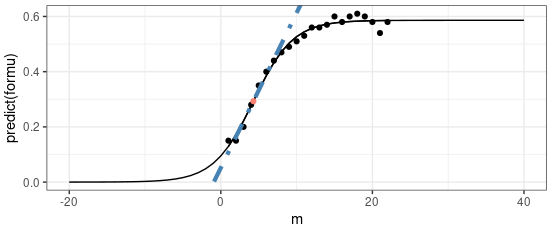

- Reaction Time-Intensity (RT-I) Functions:

- Effectively mirror equal loudness contours in humans.

- Easier to obtain than equal loudness judgments, particularly in animal subjects.

-

Factors Affecting Loudness Estimation:

- Sound Intensity: Primary factor.

- Other Acoustic Factors:

- Stimulus duration.

- Bandwidth.

- Background Noise Effect:

- Simulates loudness recruitment.

- Rapid loudness growth near threshold, but stabilizes at suprathreshold levels.

-

Study Objectives:

- Examine if RT-I functions can reliably measure loudness growth in rats.

- Obtain auditory RTs across varying:

- Stimulus intensities.

- Durations.

- Bandwidths.

- Experiments conducted in both quiet conditions and amidst background/masking noise.

-

Findings:

- Reaction time patterns across different stimulus parameters:

- Repeated consistently over several months in rats.

- Generally align with human loudness perceptual data.

- Reaction time patterns across different stimulus parameters:

-

Significance:

- Results lay foundational understanding for upcoming studies on loudness perception in animal models.

- Potential to explore loudness perceptual disorders in animals.

Introduction

Exploring Loudness Perception Beyond Traditional Methods

-

Standard Tool:

- Pure Tone Audiogram: Essential for hearing research but limited in scope.

-

Loudness Perception:

- Beyond hearing threshold, loudness perception for louder sounds is crucial.

-

Clinical Metrics:

- Uses scales like ULL and LDL where listeners rate discomfort from various sound intensities.

-

Human Psychophysical Studies:

- Equal loudness contours: Listeners compare sound loudness to a standard tone, a labor-intensive method.

Measuring Loudness Perception in Animals

-

Traditional Measures:

- LDLs and equal loudness contours: Useful for humans but impractical for animals.

-

Auditory Reaction Time (RT):

- Used as an indirect metric of loudness in animals.

- In humans, a faster RT correlates with perceived loudness.

-

Advantages of RT:

- Reliable for both normal-hearing and hearing-impaired listeners.

- Easier to obtain than traditional measures, making it useful for various species.

Certainly! I’ll further condense and clarify the content:

Loudness Perception Factors in Humans

-

Intensity:

- Main determinant, but not the sole factor.

-

Duration:

- Longer sounds (up to 300 ms) seem louder.

-

Bandwidth:

- Wider bandwidths make sounds feel louder.

-

Background Noise:

- Can mimic “loudness recruitment”, where sounds just above threshold feel quiet but get rapidly louder.

Evaluating Reaction Time-Intensity (RT-I) Functions in Rats

-

Objective:

- Check if RT-I in rats matches human patterns of perceived loudness.

-

Method:

- Measured auditory RTs in rats for various:

- Intensities

- Durations

- Bandwidths

- Conducted in quiet and with background noise.

- Measured auditory RTs in rats for various:

-

Expectations:

- If rats and humans perceive loudness similarly:

- RTs should decrease as intensity, duration, and bandwidth increase.

- RTs should rise near the hearing threshold when background noise is present.

- If rats and humans perceive loudness similarly:

Aims and Challenges in Developing an Animal Behavioral Model for Loudness Perceptual Disorders

-

Primary Goal:

- Develop a behavioral model in animals to study loudness perceptual disorders, specifically loudness recruitment and hyperacusis.

-

Challenges:

- Accounting for effects of drug or noise on hearing.

- E.g., High-dose salicylate can cause hearing loss, tinnitus, and possibly hyperacusis.

- Noise often leads to hearing loss, loudness recruitment, and potentially tinnitus and hyperacusis in some listeners.

- A successful model should distinguish:

- Loudness recruitment from hyperacusis.

- Hyperacusis from tinnitus.

- Accounting for effects of drug or noise on hearing.

-

Tinnitus-like Percept Study:

- Effect of broadband noise vs. tonal masker on RTs was studied.

- Goal: Understand the influence of a “tinnitus-like” percept on loudness growth.

- Hypothesis:

- Tinnitus-like 16 kHz masker won’t affect RT-I functions for 4 kHz tones but might impact the loudness growth of 16 kHz tones.

-

Stability of RTs in Rats:

- Beyond comparing rat RT-I functions to humans, the study aimed to test RT stability over time.

- This is crucial as animal psychoacoustic studies span weeks or months.

- A consistent loudness perception metric is needed, especially when no experimental manipulations are applied.

Result

Impact of Stimulus Duration on Auditory Reaction Time (RT)

-

Experiment Setup:

- Reaction time-intensity (RT-I) functions were measured for broadband noise bursts (BBN) across three durations: 20 ms, 100 ms, and 300 ms.

-

Main Findings:

- RTs for BBN decreased with rising stimulus intensity for all tested durations.

- Rats had quicker RTs (i.e., reacted faster) with longer stimulus durations.

- No significant interaction found between sound level and stimulus duration.

- Results imply rats perceived longer sounds as louder, similar to human perception.

-

Detailed Results:

- RTs for 300 ms BBN were significantly faster than for 100 ms and 20 ms BBN.

- Significant differences were observed:

- Between 20 ms and 300 ms BBN across all sound levels.

- Between 100 ms and 300 ms BBN at specific dB levels: 40, 50, 60, and 80 dB SPL.

|

|---|

Impact of Stimulus Bandwidth on Auditory Reaction Time (RT) in Rats

-

Hypothesis:

- Wider band stimuli would sound louder (and thus induce faster RTs in rats) compared to narrower band or pure tone stimuli, based on human data.

-

Key Findings:

- Rats reacted faster to stimuli with increased bandwidth, aligning with the hypothesis that wideband stimuli sound louder.

-

Detailed Observations:

- RTs for Broadband Noise Bursts (BBN) were faster than for 16 kHz pure tones at most sound levels, excluding 30 dB SPL.

- RTs for BBN were also faster compared to 16–20 kHz Narrow Band Noise (NBN) for specific dB levels: 30, 40, 50, and 60 dB SPL.

-

Conclusion:

- Just as with duration, these results indicate that RT is a reliable metric for loudness perception in rats, mirroring known human data on loudness perceptions of different bandwidth sounds.

|

|---|

Effects of Background Noise on Loudness Perception in Rats

-

Experiment Setup:

- Measured RT-I functions for Broadband Noise Bursts (BBN) in quiet and with low-level background noise (2-20 kHz, 60 dB SPL).

-

Main Findings:

- In the presence of background noise, rats had:

- Slower RTs for lower intensity sounds.

- Regular RTs for higher intensity sounds.

- These patterns suggest the rats experienced recruitment-like perceptions in noise.

- As intensity increased just above threshold, RT decrease was sharper in noise than in quiet, aligning with loudness recruitment patterns.

- In the presence of background noise, rats had:

-

Background Noise Effects:

- Significant effects found on RTs for lower intensity stimuli when compared to quiet conditions.

- In particular, differences were noted at 30, 40, and 50 dB SPL BBN levels.

- This indicates that, like humans, rats experience a recruitment-like loudness growth in the presence of background noise.

-

Effects of 16 kHz Masker:

- No recruitment-like effects on RTs for 4 kHz tones.

- Rats reacted slightly faster at 40 and 50 dB SPL tones with the 16 kHz masker.

- However, the effect might be due to task performance variability.

- For 16 kHz tones, the masker had a significant effect, especially at 60 dB SPL.

- This suggests that animals with tinnitus might show recruitment-like behaviors for sounds close to the tinnitus frequency.

Discussion

- RT-I functions in rats align with established human loudness perception research, suggesting they’re a valid measure of rat loudness growth.

- Their consistency over four months indicates the RT-I approach reliably reflects loudness perception in rats.

Key Findings on Noise Exposure and Hearing

-

Loudness Recruitment:

- Noise and drugs can cause hearing loss.

- This loss can lead to “loudness recruitment,” where soft sounds seem quickly loud, but this doesn’t affect louder sounds.

-

Using Rats to Understand Loudness:

- In our tests, rats exposed to background noise showed symptoms similar to loudness recruitment.

-

Hyperacusis:

- This is when everyday sounds seem too loud.

- Certain studies, including ours, used reaction times to detect hyperacusis in animals.

- Our tests found that a high aspirin dose made rats more sensitive to certain sound levels.

-

Noise Exposure’s Role:

- Extended noise exposure in rats caused both loudness recruitment and hyperacusis-like behaviors.

Reaction Time-Intensity (RT-I) as a Model for Loudness Growth:

-

Loudness Growth in Animals:

- Our RT-I conditioning model effectively maps loudness growth in animals.

- It can predict how noise or drug exposure influences loudness perception.

-

Hyperacusis vs. Loudness Recruitment:

- Hyperacusis: Faster reaction times at moderate-high sound intensities.

- Loudness Recruitment: Regular reaction times at these intensities.

- Differentiating between tinnitus and hyperacusis is crucial.

-

Studying Tinnitus:

- Prior studies on tinnitus using RT-I functions lacked comprehensive results.

- In our experiment, using a “tinnitus-like” background showed recruitment-like loudness growth for tones at tinnitus pitch. Other tones remained unaffected.

- Hyperacusis showed a different pattern than tinnitus. Thus, RT-I functions can potentially distinguish between the two.

- However, the overlap of tinnitus with hearing loss complicates this distinction.

-

Conclusion and Future Directions:

- Auditory reaction time mirrors loudness perception both in rats and humans.

- RT-I functions can screen for hearing disorders in rats post noise/drug exposure.

- Our goal is to expand this model, compare it with human loudness contours, and integrate neural and biochemical measures in future studies.

Testing the Central Gain Model: Loudness Growth Correlates with Central Auditory Gain Enhancement in a Rodent Model of Hyperacusis

Abstract

Central Gain Model of Hyperacusis

- Theory:

- Auditory input ↓ → Neuronal gain ↑ → Over-amplification & loudness ↑.

Study Objective

- Link: Sound-evoked activity changes ↔ Loudness perceptual alterations.

Methodology

- Operant Conditioning Task:

- Measure: Loudness via auditory stimuli reaction time.

- Chronic Electrophysiological Recordings:

- Locations: Auditory cortex & inferior colliculus (awake animals).

- Goal: Daily loudness perception ↔ Neurophysiological sound encoding.

Salicylate-induced Model

- Purpose: Validate the paradigm.

- Effects of high sodium salicylate doses:

- Temporary hearing loss.

- Neural hyperactivity.

- Auditory disruptions (e.g., tinnitus, hyperacusis).

Findings

- Salicylate effects:

- Alters: Loudness growth & Evoked response-intensity.

- Results:

- Consistent with: Temporary hearing loss & hyperacusis.

- Correlation: Loudness growth ↔ Sound-evoked activity (individual animals).

Conclusion

- Strong support: Central gain model of hyperacusis.

- Value: Experimental design for within-subject comparison.

Introduction

part 1

Hyperacusis

- Definition: Auditory disorder where moderate sounds → intolerably loud/painful.

- Type: Common with sensorineural hearing loss.

Central Gain Model (CGM)

- Concept: Maladaptive response in auditory system due to hearing loss.

- Mechanism:

- Central auditory system adjusts for hearing sensitivity.

- Dysregulation & central auditory pathway over-amplification → normal sounds perceived as excessively loud.

- Support:

- Accounts for major hyperacusis features.

- Strong evidence backing.

Validation Need: Relate central gain changes & loudness perception.

Human Imaging

- Findings: Hyperacusis patients → increased sound-evoked activity.

- Limitation: Can’t link neurophysiological changes & hyperacusis development.

Animal Models

- Advantage: Detailed hyperacusis examination.

- Findings: Hearing loss (due to noise/drugs) → central gain increase.

- Limitation:

- Between-group comparisons.

- Acute measurements from anesthetized subjects.

→ Focus on specific auditory areas. - Few studies link central gain & loudness.

part 2

Challenges in Hyperacusis Study

- Direct Relationship Needs:

- Objective loudness perception indicators.

- Indicators should reflect both hearing loss & hyperacusis in single animals.

- Inter-subject Variability:

- Hearing loss is a hyperacusis trigger but not a guaranteed outcome.

- Not all animals develop hyperacusis even under similar conditions.

Loudness Perception Indicator: RT-I

- RT-I: Measures loudness growth via subject’s reaction time (RT) to varied sound intensities.

- Closely linked with human loudness growth & equal loudness contours.

- Usage:

- Reflects loudness recruitment in hearing impaired humans & animals.

- Captures hyperacusis-like changes (example: rats treated with sodium salicylate).

Animal Models & Hyperacusis Variability

- Need: Relate neural hyperactivity with hyperacusis-like behavior in each animal.

- Our Approach:

- Combine psychophysical & electrophysiological methods.

- Track changes in both loudness perception & sound-evoked activity longitudinally.

Methodology

- Chronic Implants:

- Locations: Auditory cortex (AC) & inferior colliculus (IC).

- Purpose: Monitor sound-evoked activity in awake animals & avoid anesthesia issues.

- Benefit: Directly link sound encoding with daily loudness growth assessment per animal.

Validation of Combined Approach

- Test: Effect of salicylate on RT-I & neural activity in the same animals.

- Findings:

- Salicylate-induced changes in RT-I & sound-evoked activity coexist in individual animals.

- Supports the central gain model.

- Validates the combined behavioral-electrophysiological paradigm.

Result

Stable behavioral and electrophysiological measures of loudness growth

Experiment Overview

- Tested Animals: 8 rats.

- Procedure:

- Go/No-go operant conditioning paradigm.

- Electrodes chronically implanted in primary AC & central nucleus of the IC.

Observations

-

LFP Tuning Curves:

- Well-tuned for frequency.

- AC & IC electrodes matched for characteristic frequency in each hemisphere.

-

Baseline RT-I & LFP I/O Functions (broadband noise burst 30–90 dB SPL):

- RTs:

- Decreased from ~325 ms (30 dB SPL) to ~140 ms (90 dB SPL).

- AC I/O Functions:

- Amplitude increased from ~30 mV (30 dB SPL) to ~70 mV (90 dB SPL).

- IC I/O Functions:

- Amplitude grew from ~40 mV (30 dB SPL) to ~125 mV (90 dB SPL).

- RTs:

-

Consistency:

- No significant differences observed across baseline sessions in RT-I, AC, or IC I/O functions.

-

Conclusion:

- Behavioral & electrophysiological responses are stable without any explicit manipulation.

Salicylate-induced hyperacusis and hyperactivity

Post-Baseline Testing with Sodium Salicylate (SS) Treatment

-

Procedure:

- Animals received 200 mg/kg SS injection (i.p.).

- Assessments made 2 hours post-SS and again after 24 hours.

-

Data Analysis:

- RTs & AC/IC LFP amplitudes normalized to maximum average baseline values.

-

Observations 2 Hours Post-SS:

- Low-Intensity Noise Bursts (30 dB SPL):

- RTs → Slower than baseline.

- AC/IC Amplitudes → Smaller than baseline.

- Interpretation: Cochlear hearing loss likely from SS-mediated ototoxicity.

- Moderate-to-High Intensities (70-90 dB SPL):

- RTs → Faster than baseline → Suggests sounds perceived louder (possible hyperacusis).

- AC/IC Amplitudes → Larger than baseline → Indicates enhanced central gain.

- Low-Intensity Noise Bursts (30 dB SPL):

-

Observations 24 Hours Post-SS:

- Both behavioral and electrophysiological changes observed at 2 hours post-SS were reversed.

- Likely due to drug washout.

Salicylate-induced gain modulation

Results Analysis Based on Fig. 2A-C

-

Observation:

- SS alters loudness growth & LFP responses.

- At low intensities: Slower RTs & decreased LFPs.

- At high intensities: Faster RTs & enhanced LFPs.

- Result: Steeper slope of response functions → Central gain theory hallmark.

-

Response Gain Assessment - Approach 1:

- Fit RT-I & AC/IC LFP response functions with linear regression.

- Check slope changes (normalized response/dB) due to SS.

- 2 hours post-SS:

- RT, AC, IC functions → Greater slopes than baseline.

- 24 hours post-SS:

- Slopes → No significant deviation from baseline.

-

Response Gain Assessment - Approach 2:

- Transform baseline RT/AC/IC response function to post-SS equivalent.

- Scatter plots depict change in response magnitude at each intensity post-SS.

- Interpretation:

- Below 45° line → Decreased response post-SS.

- Above 45° line → Increased response post-SS.

-

Scatter Plot Analysis:

- Plots fitted with linear regression (2 & 24 hours post-SS).

- Slope (R Gain) describes magnitude of gain modulation by SS:

- ( R \text{ Gain} > 1 ) → Enhanced response gain.

- ( R \text{ Gain} < 1 ) → Decreased response gain.

- ( R \text{ Gain} = 1 ) → No change in response gain.

-

Key Findings:

- Baseline sessions: Response gain consistent across RT-I or AC/IC LFP functions.

- 2 hours post-SS: Slope > 1 for RT, AC, IC → Increased response gain.

- More robust gain increase observed in AC than IC.

- 24 hours post-SS: Response growth rate reverted to baseline.

Within-subject relationship between RT, AC and IC gain changes

Results Analysis Based on Fig. 2 & 3

-

Salicylate’s Effects:

- Alters response gain for RT and LFP I/O functions.

- Central gain enhancement linked with altered loudness perception.

-

Individual Animal Analysis (Fig. 3):

- Animal with substantial RT-I alteration post-SS also had pronounced changes in AC/IC I/O functions.

- Animal with modest RT-I alteration post-SS exhibited minor changes in AC/IC I/O functions.

- RT-I & AC/IC I/O functions reverted to baseline levels 24h post-SS in both cases.

-

Subject-by-Subject Analysis:

- Behavioral & electrophysiological changes due to salicylate are correlated within individual animals.

- Majority of subjects exhibited increased response gain (R G +) post-SS.

- RT-I function: 7/8 animals had significant change.

- AC I/O function: 6/8 animals had significant increase.

- IC I/O function: 5/8 animals had significant change.

- All gain changes reverted to baseline 24h post-SS.

-

Hypothesis Testing:

- Correlation found between individual AC & RT-I and between individual IC & RT-I response gains.

- AC and RT-I gain changes showed close concordance in magnitude.

-

Distinguishing Hyperacusis from Loudness Recruitment:

- Increase in response gain doesn’t necessarily indicate hyperacusis.

- Response gain doesn’t determine if responses overshoot baseline.

- Changes in loudness & neural activity post-SS were significantly correlated.

- Decreased sensitivity to low-intensity sounds post-SS linked to response changes in AC and IC.

- Hyperacusis-like behavior at moderate-to-high intensities more correlated with cortical than subcortical response changes.

Discussion

Discussion:

→ Objective: Link hyperacusis & central gain enhancement.

Methods:

- Psychophysical-electrophysiological approach.

- Stable loudness & auditory-evoked functions from animals.

- Assessed salicylate effects on RT-I & AC/IC I/O.

Findings:

- Salicylate: Alters RT-I & AC/IC I/O → Suggests hearing loss & hyperacusis.

- Loudness & sound-evoked activity affected by salicylate are correlated.

Significance:

- Supports central gain model of hyperacusis.

- Within-subject comparisons valuable; inter-subject variability is a strength.

Mutations causing syndromic autism define an axis of synaptic pathophysiology

Abstraction

Topic:

Tuberous sclerosis complex (TSC) & fragile X syndrome (FXS): Genetic diseases with intellectual disability & autism.

Hypothesis:

- Cause: Mutations in genes regulating neuronal protein synthesis.

- Excessive protein synthesis might be a core mechanism for intellectual disability & autism.

Method & Findings:

- Used: Electrophysiological & biochemical assays in the hippocampus of Tsc2+/- and Fmr1-/y mice.

- Result: Synaptic dysfunction due to mutations falls at opposite ends of a physiological spectrum.

- Synaptic, biochemical, cognitive defects in mutants can be corrected by modulating metabotropic glutamate receptor 5 (mGluR5) in opposite directions.

- Deficits vanish when mice carry both mutations.

Conclusion:

- Optimal synaptic plasticity & cognition occur within a specific range of mGluR5-mediated protein synthesis.

- Deviating from this range results in shared behavioural impairments.

Introduction

Background:

- >1% have Autism Spectrum Disorder (ASD).

- 50% of them also have intellectual disability (ID).

- Main cause: Unknown.

- Some known: Genetic syndromes.

Fragile X Syndrome (FXS):

- Caused by FMR1 gene silencing.

- Fmr1 knockout mouse: ↑ protein synthesis via mGluR5.

- Inhibiting mGluR5 corrects FXS.

Hypothesis:

- Some ASD & ID from gene mutations affecting synaptic mRNA.

- Altered protein synthesis common in autism & ID?

Study Aim:

- Examine: TSC mutation → same protein synthesis abnormalities as FXS?

- If yes, one treatment could benefit both disorders.

Result

TSC mutations affect synaptic function

Reasons:

- Single-gene disorder → ASD & ID symptoms like FXS.

- Affected gene in receptor-to-mRNA translation pathway.

- Valid mouse models available.

- Some mouse models respond to protein synthesis treatments.

TSC Details:

- Caused by TSC1 or TSC2 gene mutations.

- Form TSC1/2 complex.

- TSC1/2 inhibits Rheb → specific for mTOR in mTORC1 complex.

- Excessive mTORC1 → ↑ mRNA translation & cell growth.

- TSC symptoms: Hamartoma growths due to functional allele inactivation.

- Some TSC neurological symptoms: Tumor growth in cortex.

- Other symptoms (cognitive & autism): Abnormal synaptic signaling.

Mouse Model:

- Tsc1 or Tsc2 mutants → hippocampus-dependent learning/memory deficits.

- No brain tumors or seizures.

- Used Tsc2+/- model.

- TSC2 mutations more severe & common in humans.

- Tsc2+/- mice treated with mTORC1 inhibitor (rapamycin) → improved hippocampal memory.

- Potential drug treatment for TSC & FXS.

Hypothesis:

- TSC synaptic dysfunction → ↑ protein synthesis (due to ↑ mTORC1).

- mTORC1 links mGluR5 to protein synthesis.

- mTOR ↑ protein synthesis also in Fmr1-/y mouse (controversial).

mGluR-LTD:

- Electrophysiological measure of local mRNA translation.

- Exaggerated LTD in Fmr1-/y → led to mGluR FXS theory.

- Study: Examine mGluR-LTD in Tsc2+/- mouse hippocampus.

Protein synthesis and mGluR-LTD in Tsc2+/- mice

-

LTD Induction:

- Used Gp1 mGluRs (mGluR 1 & 5) activation with DHPG in hippocampal slices.

- Tsc2+/- mice showed deficient DHPG-induced LTD compared to WT (Fig. 1a).

- Similar deficit observed with patterned electrical stimulation (Fig. 1b).

-

Tsc2+/- Synaptic Function:

- Basal synaptic transmission in CA1 was normal (Supplementary Fig. 1).

- NMDA-receptor-dependent LTD was also similar between Tsc2+/- and WT (Fig. 1c).

- DHPG-induced ERK1/2 phosphorylation (indicator of Gp1 mGluR signalling) unchanged in Tsc2+/- (Fig. 1d).

- Concluded: Deficit in mGluR-LTD isn’t from global synaptic or Gp1 mGluR signalling disruption.

-

LTD Mechanisms:

- Two mechanisms in WT:

- Reduced presynaptic glutamate release probability.

- Reduced postsynaptic AMPA receptors.

- Postsynaptic change needs immediate mRNA translation in hippocampal pyramidal neurons.

- Cycloheximide (protein synthesis inhibitor) reduced LTD in WT (Fig. 2a) but not in Tsc2+/- (Fig. 2b).

- Suggests: Tsc2+/- has selective loss of protein-synthesis-dependent component of LTD.

- Two mechanisms in WT:

-

Comparison with Fmr1-/y Mouse:

- Tsc2+/-'s electrophysiological results contrast Fmr1-/y, where mGluR-LTD is enhanced.

- Fmr1-/y has increased basal mRNA translation downstream of mGluR5.

- Tsc2+/- showed decreased [35S] methionine/cysteine protein incorporation under basal conditions (Fig. 2d).

-

Arc Protein:

- Reduced Arc expression in Tsc2+/- hippocampal slices (Fig. 2e).

- Arc is synthesized in response to Gp1 mGluR activation and required for mGluR-LTD.

- Significant reduction in Arc translation in Tsc2+/- hippocampus (Fig. 2f).

- Indicates: mGluR-LTD deficiency in Tsc2+/- due to decreased translation of LTD-stabilizing proteins, including Arc.

LTD deficit caused by excess mTOR activity

- Goal: Understand if the Tsc2+/- mutation’s impact on mGluR-LTD is due to unchecked mTOR activity.

- Key Findings:

- Rapamycin restored mGluR-LTD in Tsc2+/- to normal levels.

- This treatment didn’t affect the WT mice.

- The rescue in Tsc2+/- was due to restored protein synthesis.

- Conclusion: Uncontrolled mTOR activity in Tsc2+/- hinders the protein synthesis needed for mGluR-LTD.

Effect of mGluR5-positive allosteric modulation

mGluR5’s Role in Tsc2+/- Model of TSC:

-

Background:

- FXS issues are fixed by lowering mGluR5 signaling.

- Thought of boosting mGluR5 signaling for TSC.

-

mGluR5 PAM’s Impact:

- A PAM boosts mGluR-LTD in Tsc2+/- mice.

- This corrects the protein-dependent part of LTD.

- PAM (CDPPB) also fixes protein and Arc synthesis issues.

-

Behavioral Effects:

- Tsc2+/- mice struggle in a fear task.

- mGluR5 and new protein synthesis are crucial for this.

- CDPPB treatment before training helps Tsc2+/- mice.

-

Conclusion: Boosting mGluR5 might help treat TSC cognitive problems.

Fmr2/y and Tsc21/2 mutations cancel each other

Contrasting Effects of FXS and TSC Mutations on mGluR5 and Memory:

-

Initial Findings:

- FXS and TSC mutations show opposite impacts on protein-synthesis-dependent LTD.

- They respond oppositely to mGluR5 treatments.

-

Experiment with Combined Mutations:

- Introduced an Fmr1 deletion to Tsc2+/- background.

- mGluR-LTD was reduced in Tsc2+/- and increased in Fmr1-/y.

- Mice with both mutations showed mGluR-LTD similar to WT.

-

Memory Impairment Comparison:

- Tsc2+/- and Fmr1-/y have similar cognitive issues, despite opposite synaptic alterations.

- Both have a context discrimination memory deficit.

- However, double mutants don’t show this deficit, suggesting both mutations might counteract each other’s effects on behavior.

Discussion

LTD, Protein Synthesis, and Genetic Disorders:

-

Context:

- LTD and mGluR5-related protein synthesis are significant in FXS.

- FXS arises from the absence of FMRP, an mRNA-binding protein inhibiting translation.

- In the Fmr1-/y mouse, there’s heightened protein synthesis and exaggerated LTD via an mGluR5-ERK1/2 pathway.

-

mTOR Significance:

- Elevated mTOR activity suppresses protein synthesis vital for LTD in Tsc2+/- mice.

- Hyperphosphorylation of FMRP or increased translation of certain mRNAs might explain this suppression.

- Arc, crucial for mGluR5-related long-term plasticity, is under-translated in Tsc2+/- mice.

- mGluR-LTD differences in Tsc2+/- and Fmr1-/y mice suggest distinct regulation by FMRP and TSC1/2.

-

Potential Treatments:

- Rapamycin, though beneficial, has limitations due to immunosuppressive properties.

- mGluR5 PAMs might target synaptic mechanisms causing cognitive and behavioral issues in TSC.

-

Implications for ASD:

- TSC and FXS are significant genetic risk factors for ASD and intellectual disability.

- While Fmr1 mutation leads to exaggerated protein synthesis and LTD, Tsc2 mutation causes the opposite. Both can be balanced out in combined mutations.

- This suggests that ASD’s genetic causes might produce similar effects by deviations from the norm.

- Therapies for one type of ASD might not work for all, emphasizing personalized treatments.

Deletion of Fmr1 from Forebrain Excitatory Neurons Triggers Abnormal Cellular, EEG, and Behavioral Phenotypes in the Auditory Cortex of a Mouse Model of Fragile X Syndrome

Abstract

Fragile X Syndrome and Sensory Processing Deficits:

-

Context:

- Fragile X syndrome (FXS) is a primary genetic cause of autism, marked by sensory processing anomalies.

- In humans with FXS and Fmr1 knockout (KO) mouse model: EEG shows enhanced resting gamma power and diminished sound-evoked gamma synchrony.

-

Matrix Metalloproteinase-9 (MMP-9):

- Past studies indicate elevated MMP-9 levels might influence these EEG anomalies by affecting perineuronal nets (PNNs) around parvalbumin (PV) interneurons in the auditory cortex of Fmr1 KO mice.

-

Effects of Fmr1 Deletion in Excitatory Neurons:

- Cortical MMP-9 gelatinase activity, mTOR/Akt phosphorylation, and resting EEG gamma power increase.

- Density of PV/PNN cells decrease.

- CreNex1 /Fmr1Flox/y cKO mice show heightened locomotor activity but not anxiety-like behaviors.

-

Implications:

- FMRP changes in cortical excitatory neurons can produce cellular, electrophysiological, and behavioral phenotypes in Fmr1 KO mice.

- Suggests local cortical circuit abnormalities play a role in sensory processing deficits in autism spectrum disorders.

Fragile X Syndrome and Sensory Processing Deficits: An In-depth Study

Introduction

-

Introduction & Background:

- Fragile X syndrome (FXS) is a monogenic form of autism spectrum disorders (ASD).

- Caused by a CGG repeat expansion in the Fmr1 gene, leading to downregulation of fragile X mental retardation protein (FMRP).

- Symptoms include anxiety, intellectual disability, and abnormal sensory processing, particularly auditory hypersensitivity.

-

Auditory Hypersensitivity in FXS:

- Both humans with FXS and Fmr1 knockout (KO) mice exhibit auditory hypersensitivity.

- Electroencephalographic (EEG) studies in these subjects have shown increased resting EEG gamma band power, which could underlie sensory hypersensitivity.

-

The Role of Matrix Metalloproteinase-9 (MMP-9):

- MMP-9 levels are elevated in FXS brains and could affect the development of parvalbumin (PV)-expressing inhibitory interneurons.

- MMP-9 is secreted from various cell types including astrocytes and neurons.

- It can also mediate changes in synaptic functions through the PI3K/Akt/mTOR pathway.

-

Cell-Specific Effects:

- FMRP is expressed in multiple levels and cell types in the auditory pathway.

- The origin and cell type specificity of abnormal EEG recordings are still unknown.

-

Objective of the Current Study:

- To understand the impact of deleting Fmr1 specifically from forebrain excitatory neurons.

-

Findings:

- Deletion of FMRP from forebrain excitatory neurons was sufficient to elicit FXS-associated symptoms.

- This includes enhanced MMP-9 activity, increased mTOR/Akt signaling, impaired PV/PNN expression, and hyperactive behaviors.

-

Implications:

- The study suggests that FMRP in excitatory neurons is critical for normal cortical activity.

- Highlights novel mechanisms potentially leading to sensory hypersensitivity in FXS and possibly other forms of ASD.

Result

- Goals:

- Check if issues in auditory cortex of Fmr1 KO mice persist in adulthood.

- Examine effects of FMRP deletion on brain and behavior.

- Key Results:

- Reduced density of PV cells in layer 4 of auditory cortex in Fmr1 KO mice.

- Lower density of WFA+ PNN cells in both layer 4 and 2/3 in Fmr1 KO mice.

- Poor formation of PNNs around PV cells in Fmr1 KO mice.

- Implications:

- The observed deficits are long-lasting, suggesting they may cause enhanced sound sensitivity in Fmr1 KO mice.

FMRP Immunoreactivity Was Significantly Reduced in Excitatory Neurons of Auditory Cortex of Adult CreNex1 /Fmr1Flox/y cKO Mice

- Method:

- Used CreNex1 and Fmr1flox/flox KO mice to specifically delete FMRP in forebrain excitatory neurons.

- Key Results:

- Significant reduction in FMRP in the auditory cortex of CreNex1/Fmr1Flox/y cKO mice compared to controls.

- No significant change in cell density in the auditory cortex.

- No significant changes in FMRP expression in other parts of the auditory pathway like the inferior colliculus and auditory thalamus.

- Implications:

- The deletion of FMRP is specific to forebrain excitatory neurons in the auditory cortex and doesn’t affect other regions, confirming the targeted nature of the genetic manipulation.

Deletion of FMRP from Excitatory Neurons Reduces PV, PNN, and PV/PNN Colocalization in the Auditory Cortex of Adult CreNex1 /Fmr1 Flox/y cKO Mice

-

Method:

- Studied cell density in the auditory cortex of specific knockout mice (CreNex1/Fmr1Flox/y cKO) and control mice (Fmr1Flox/y).

-

Results:

- Fewer PV cells in knockout mice in two brain layers (L4 and L2/3).

- Fewer WFA+ PNN cells in the same layers in knockout mice.

- Less overlap of PV and WFA+ PNN cells in knockout mice in both layers.

-

Implications:

- Loss of FMRP in excitatory neurons affects these cells.

- This could disrupt overall brain network function.

Total Aggrecan Levels Are Reduced, While Cleaved Aggrecan Levels and Gelatinase Activity Are Enhanced in the Auditory Cortex of Adult CreNex1 /Fmr1 Flox/y cKO Mice

-

Method:

- Conducted a gelatinase activity assay and measured aggrecan levels in the auditory cortex of specific mouse models.

-

Results:

- Higher gelatinase activity in both Fmr1 KO and Cre Nex1/Fmr1 Flox/y cKO mice compared to controls.

- Lower levels of full-length aggrecan and higher levels of cleaved aggrecan in both Fmr1 KO and Cre Nex1/Fmr1 Flox/y cKO mice.

- Increased ratio of cleaved aggrecan to total aggrecan in these mice.

-

Implications:

- The increased gelatinase activity, likely due to elevated MMP-9 levels, may contribute to the loss of PNNs.

- The cleavage of aggrecan, a key component of PNNs, is also affected.

- The loss of FMRP in excitatory neurons may underlie these molecular changes, affecting overall neural network integrity.

Deletion of FMRP from Excitatory Neurons Triggers a Decrease in PV Levels, While Akt and mTOR Phosphorylation Is Increased in Auditory Cortex of Adult CreNex1 /Fmr1 Flox/y cKO Mice

Key Findings on PV Levels and Akt/mTOR Signaling

-

Method:

- Measured levels of Parvalbumin (PV) and phosphorylated forms of Akt and mTOR in the auditory cortex of specific mouse models.

-

Results:

- Significant decrease in PV levels in the auditory cortex of Fmr1 KO and Cre Nex1/Fmr1 Flox/y cKO mice.

- Higher levels of phosphorylated (i.e., active) forms of Akt and mTOR in these mouse models compared to their controls.

-

Implications:

- The decrease in PV levels is consistent with earlier findings in autism mouse models and might be linked to network dysfunction.

- Enhanced Akt/mTOR signaling could contribute to synaptic changes and hyperexcitability seen in FXS and other autism spectrum disorders.

- The deletion of FMRP in excitatory neurons is sufficient to trigger these molecular changes, pointing to its pivotal role in the auditory cortex of adult mice.

Resting EEG Gamma Power Is Enhanced in the Auditory Cortex of Adult CreNex1 /Fmr1 Flox/y cKO Mice

Key Findings on Impaired Neural Oscillations and Local Circuit Defects

-

Objective:

- To determine if deficits in forebrain excitatory neurons cause abnormal neural oscillations similar to global Fmr1 KO mice.

-

Methods:

- Baseline EEG raw power in auditory cortex examined for Cre Nex1/Fmr1 Flox/y cKO mice (n=9) and control Fmr1Flox/y mice (n=9).

- Analyzed various frequency bands during a 5-minute resting period.

-

Results:

- Enhanced high-frequency oscillations observed in the auditory cortex of Cre Nex1/Fmr1 Flox/y cKO mice.

- Significant increase in low gamma power (30-55 Hz) in the auditory cortex of these mice.

-

Implications:

- The abnormal low gamma power likely stems from local circuit defects, similar to global Fmr1 KO mice.

- These local circuit defects may be related to observed increases in gelatinase activity and reduced PV+ cell density and WFA+ PNNs around PV+ neurons.

- The results suggest that specific types of neurons may be critical for the neural oscillation abnormalities observed in FXS and potentially other autism spectrum disorders.

This study adds to the understanding that local cortical circuit abnormalities, possibly related to impaired PV+ interneuron function, contribute to neural oscillation deficits in FXS.

Gamma Synchronization Is Not Affected in Adult CreNex1 /Fmr1 Flox/y cKO Mouse Auditory Cortex

Key Findings on Phase Locking and Gamma Synchronization

-

Objective:

- To investigate if increased baseline gamma in Cre Nex1/Fmr1 Flox/y cKO mice impacts the consistency of sound-evoked gamma synchronization.

-

Methods:

- Used “chirp” stimuli with varying modulation frequencies, both up and down, presented 300 times each.

- Employed Inter-Trial Phase Coherence (ITPC) analysis to measure phase consistency across trials.

-

Results:

- Despite increased baseline gamma in Cre Nex1/Fmr1 Flox/y cKO mice, there were no significant differences in gamma band ITPC compared to controls.

- Similar patterns observed for both up- and down-chirps.

-

Implications:

- The lack of difference in gamma ITPC suggests that the gamma synchronization deficits in global Fmr1 KO mice are not solely due to excitatory neurons in the forebrain.

- This opens up the possibility that other cell types in the cortex or subcortical sites could be responsible for these deficits.

The study suggests that while local circuit defects may contribute to baseline gamma power, they may not be the sole factor affecting gamma synchronization in response to auditory stimuli in FXS.

Increased Non–Phase-Locked STP Is Observed in the Auditory Cortex of Adult CreNex1 /Fmr1 Flox/y cKO Mice during Chirp Stimulation

- Studied gamma power in Cre Nex1/Fmr1 Flox/y cKO mice.

- Found increased lower gamma power.

- Suggests local circuit issues.

Induced Power Is Significantly Enhanced in the Auditory Cortex of Adult CreNex1 /Fmr1 Flox/y cKO Mice

- Tested auditory cortex responses to noise bursts at 4 Hz and 0.25 Hz rates.

- Cre Nex1/Fmr1 Flox/y cKO mice showed reduced phase locking in the beta range (20-30 Hz).

- Increased “ongoing” response was observed in the beta to low gamma range (10-50 Hz).

- These effects persisted in repeated sound stimulation.

- Results suggest increased variability and reduced suppression of ongoing activity in cKO mice.

Excitatory Neuron-Specific Adult CreNex1 /Fmr1 Flox/y cKO Mice Display Increased Locomotor Activity, but No Anxiety-Like Behavior

- Mice were tested for activity and anxiety using elevated plus maze and open field (OF) tests.

- Cre Nex1/Fmr1 Flox/y cKO mice showed more arm entries and higher speed, indicating increased locomotor activity.

- No difference was observed in time spent in open arms, suggesting no change in anxiety levels.

- In the OF test, cKO mice also crossed more lines and moved faster, confirming increased activity.

- No significant difference in time spent in center or thigmotaxis, again suggesting no change in anxiety.

- Conclusion: Deleting FMRP from forebrain excitatory neurons increases activity but doesn’t affect anxiety-like behaviors.

Discussion

- Study aims to understand sensory processing issues in Fragile X Syndrome (FXS), a genetic cause of Autism Spectrum Disorder (ASD).

- Deleting Fmr1 from forebrain excitatory neurons causes abnormal EEG patterns in adult auditory cortex.

- This deletion also increases gelatinase activity, affecting Perineuronal Nets (PNNs) around Parvalbumin (PV) neurons.

- PV neurons are crucial for sensory processing; their dysfunction may underlie sensory issues in FXS.

- The study also finds higher mTOR/Akt phosphorylation in the cortex, suggesting altered signaling pathways.

- Reduced excitation to PV neurons may lead to their decreased activity and function.

- Low-gamma band power in auditory cortex is specifically increased; this could influence sensory and cognitive processes.

- Both cortical and sub-cortical structures likely contribute to auditory processing deficits in FXS.

- Future research is needed to explore effects of Fmr1 deletion in other brain areas and cell types for a system-level understanding.

Role of Enhanced Gelatinase Activity in CreNex1 /Fmr1Flox/y cKO Mice

The study elaborates on the intricate relationship between the loss of the FMRP protein and various neural and behavioral phenomena in Fragile X Syndrome (FXS). Here’s a breakdown:

Molecular Mechanisms

- Perineuronal Nets (PNNs) and Parvalbumin (PV) Neurons: PNNs surround PV neurons and are crucial for their function. Aggrecan, a component of PNNs, is degraded by gelatinases (MMP-2, MMP-9), affecting the structure and function of PNNs.

- Gelatinase Activity: The study found increased gelatinase activity in the auditory cortex of mice lacking FMRP, indicating that this may contribute to impaired PNN formation.

- Signaling Pathways: Increased gelatinase activity can also affect the mTOR and Akt signaling pathways, which are implicated in FXS and regulate neuronal excitability.

Auditory Cortex and Sensory Processing

- MMP-9 and Sensory Responses: Deletion or reduction of MMP-9 activity in mice normalized auditory responses and PNN formation, highlighting its therapeutic potential.

- Subcortical Contributions: While the study indicates cortical deficits, it also suggests that subcortical areas may contribute to the observed abnormalities.

Behavioral Aspects

- Locomotor Activity: Mice with FMRP deletion in forebrain excitatory neurons showed increased locomotor activity but no anxiety-like behaviors.

- Role of FMRP in Other Areas: FMRP loss in other brain regions like the hippocampus may contribute to other FXS symptoms like learning and memory deficits.

Future Directions

- Astrocytes and MMP-9: The study proposes to investigate how astrocytes may be involved in regulating MMP-9 activity and PNN formation.

- Multi-Electrode EEGs: To get a comprehensive understanding, the study recommends exploring electrocortical activity in different brain areas.

Overall, the study provides a multi-faceted understanding of how FMRP loss impacts neural circuits and behaviors, offering potential therapeutic targets like MMP-9 for FXS.

Certainly! Here’s a more elegant and concise summary of the research findings and their implications.

Conclusion

Key Insights

-

Parvalbumin Neurons: Deletion of the Fmr1 gene in forebrain excitatory neurons impinges upon the integrity and function of parvalbumin-positive (PV+) inhibitory neurons.

-

Matrix Enzymology: Elevated activity of the enzyme MMP-9 remodels the extracellular scaffolding around PV+ neurons, potentially altering cellular signaling cascades.

-

Electrophysiological Nuances: The study discerns a specific alteration in resting low-gamma EEG power, correlated with hyperactive behaviors but not with anxiety.

-

Symptomatic Specificity: The research delineates that cortical deficits are responsible for some, but not all, features of Fragile X Syndrome, underscoring a nuanced impact of the Fmr1 deletion.

Clinical Implications

- The findings elegantly illuminate avenues for targeted therapeutic strategies, offering the prospect of interventions honed to specific cellular actors and neural circuits implicated in Fragile X Syndrome.

By delving into the intricacies of cellular and circuit-level changes, this study enriches our understanding of Fragile X Syndrome and opens new horizons for targeted therapeutic interventions.