Support Vector Machine

What is Support Vector Machine

SVM was developed in the 1990s by Vladimir Vapnik and his colleagues. The development of SVM was rooted in statistical learning theory. It introduced the concept of finding the maximum margin hyperplane to separate classes effectively, with extensions to handle non-linear data through kernel functions. SVM gained popularity due to its ability to create powerful classifiers, especially in high-dimensional feature spaces.

Compare to Random Forest

Random Forest is an ensemble method that combines multiple decision trees to improve accuracy and reduce overfitting, handling both linear and non-linear data well. It’s good for large datasets and provides feature importance but is less interpretable.

SVM finds the optimal hyperplane to separate classes by maximizing the margin. It works well for smaller, high-dimensional datasets but is computationally expensive for large datasets and harder to interpret.

Compare to Linear Regression

The decision function of Support Vector Machine (SVM) looks very similar to a linear function—and indeed, it shares common elements with linear regression. However, the main differences lie in their objectives and the way they handle data:

Similarities

- Linear Function Form: Both SVM and Linear Regression use a linear function of the form:

$$

f(x) = w_1 x_1 + w_2 x_2 + \cdots + w_k x_k + b

$$

Where $ w_i $ are the weights, $ x_i $ are the features, and $ b $ is the bias term. - Weight Optimization: Both models optimize the weights ($ w $) to achieve their goals.

Key Differences

-

Objective Function:

- Linear Regression: The goal is to minimize the error (typically the mean squared error) between predicted and actual values. It aims to find the line (or hyperplane) that best fits the data points by minimizing the difference between predictions and true values.

- SVM: The goal is to maximize the margin between different classes. SVM seeks to find a hyperplane that not only separates the classes but does so with the largest possible gap between the nearest points of each class (called support vectors). This makes the decision boundary as robust as possible against errors or noise.

-

Loss Function:

- Linear Regression: Uses squared loss to penalize errors, which means that even small deviations contribute to the overall loss.

- SVM: Uses a hinge loss function for classification, which penalizes misclassifications and ensures a margin of separation. The loss function focuses more on correctly classifying data points with maximum confidence.

-

Problem Type:

- Linear Regression: Primarily used for regression problems, where the goal is to predict a continuous output.

- SVM: Primarily used for classification (though it can be adapted for regression as SVR), where the goal is to classify data points into different categories. In SVM, the function output is interpreted using a sign function, where:

$$

f(x) = w^T x + b \Rightarrow \text{classify as } \begin{cases}

+1, & \text{if } f(x) > 0 \\

-1, & \text{if } f(x) < 0

\end{cases}

$$

-

Margin and Support Vectors:

- Linear Regression: There is no concept of a margin or support vectors in linear regression. It simply finds the line of best fit for all data points.

- SVM: Introduces the concept of margin, which is the distance between the hyperplane and the closest data points from each class. These closest points are called support vectors, and they are crucial to defining the decision boundary.

-

Use of Kernels (Non-linearity):

- Linear Regression: Strictly a linear model. To handle non-linearity, you would have to explicitly add polynomial features or transform the features.

- SVM: Supports kernel tricks (such as polynomial or radial basis function kernels) to project data into higher dimensions, allowing it to separate data that isn’t linearly separable in its original space. This feature makes SVM more powerful for complex, non-linear classification problems.

Summary

- Linear Regression: Minimizes prediction error for a best-fit line, used for regression.

- SVM: Maximizes the margin to find an optimal separating hyperplane, used for classification.

- While both use linear functions, SVM is fundamentally about classification and margin maximization, whereas linear regression focuses on minimizing the difference between predicted and actual continuous values. SVM also handles non-linearity more effectively through kernels, making it more versatile for complex datasets.

Overview of SVM

- Decision Boundary: $w^T x + b$.

- Classification: $f(x) = sign(w^T x + b)$

- Cost function: Training error cost + $\lambda$ penalty

| Number of Features | Decision Boundary Equation | Classification Equation |

|---|---|---|

| 1 Feature | $ w_1 x_1 + b = 0 $ | $ f(x) = \text{sign}(w_1 x_1 + b) $ |

| 2 Features | $ w_1 x_1 + w_2 x_2 + b = 0 $ | $ f(x) = \text{sign}(w_1 x_1 + w_2 x_2 + b) $ |

| $ k $ Features | $ w_1 x_1 + w_2 x_2 + \cdots + w_k x_k + b = 0 $ | $ f(x) = \text{sign}(w_1 x_1 + w_2 x_2 + \cdots + w_k x_k + b) $ |

What does $w^T$ mean

Explanation:

- A vector $ w $ is typically represented as a column vector, meaning it has multiple rows and a single column.

- $ w^T $ is the transpose of $ w $, which means converting a column vector into a row vector, or vice versa.

Mathematical Notation:

- If $ w $ is a column vector with elements: $$ w = \begin{bmatrix} w_1 \\ w_2 \\ \vdots \\ w_n \end{bmatrix} $$

- Then the transpose $ w^T $ is w row vector: $$ w^T = \begin{bmatrix} w_1 & w_2 & \cdots & w_n \end{bmatrix} $$ In SVM or machine learning, the transpose is often used to indicate a dot product operation when combined with another vector or matrix. For example, if you have: $w^T x $, it means you're calculating the dot product of vector $ w $ and vector $ x $, which is a scalar value used in calculating distances, projections, or in constructing decision boundaries in algorithms like SVM.

Features

$$

f(\mathbf{x}) = \text{sign}(\mathbf{w}^T \mathbf{x} + b)

$$

where

$$

\mathbf{x} = \begin{bmatrix} x_0 \ x_1 \end{bmatrix}, \quad \mathbf{w} = \begin{bmatrix} w_0 \ w_1 \end{bmatrix}, \quad \text{and} \quad b \text{ is a scalar.}

$$

Boundary

The boundary condition is given by:

$$

\begin{bmatrix} w_0 & w_1 \end{bmatrix} \begin{bmatrix} x_0 \ x_1 \end{bmatrix} + b = 0

$$

Solving for $ x_1 $:

$$

w_0 x_0 + w_1 x_1 + b = 0

$$

$$

x_1 = -\frac{w_0}{w_1} x_0 - \frac{b}{w_1}

$$

Classification

The classification function is:

$$

y = \begin{cases}

1 & \text{if } x_1 \geq -\frac{w_0}{w_1}x_0 - \frac{b}{w_1} \\

-1 & \text{if } x_1 < -\frac{w_0}{w_1}x_0 - \frac{b}{w_1}

\end{cases}

$$

Training Cost

The training cost in SVM refers to the computational and resource-related costs involved in training the model, which is an important consideration when choosing an algorithm, especially for larger datasets. SVM’s training cost is influenced by its optimization problem, which involves finding the hyperplane that maximizes the margin while correctly classifying the training data (or with minimal misclassification for soft margins).

Training Cost in SVM

-

Optimization Complexity:

- SVM training involves solving a quadratic optimization problem to find the best hyperplane.

- This process is complex and takes more computation, especially with non-linear kernels.

-

Time Complexity:

- Linear SVM: Training time is between $O(n * d)$ and $O(n^2 * d)$, where $ n $ is the number of data points and $ d $ is the number of features.

- Non-linear Kernel SVM: Training complexity is approximately $O(n^2)$ to $O(n^3)$, making it very expensive for large datasets.

-

Memory Usage:

- With kernels, SVM stores a kernel matrix of size $ n \times n $, which uses a lot of memory if $ n $ is large.

-

Support Vectors:

- More support vectors means more computation during both training and prediction. Complex datasets often need more support vectors.

Why Care About Training Cost?

- Scalability: SVM can become impractical for large datasets due to the high cost in terms of time and memory.

- Resources: It requires substantial CPU and memory, limiting its use on resource-constrained systems.

- Algorithm Selection: For small to medium datasets, SVM works well. For large datasets, other methods like Random Forest or SGD may be better.

Reducing Training Cost

- Linear SVM: Use for linearly separable data—it has lower complexity.

- Approximations: Use SGDClassifier or kernel approximations for faster training.

- Data Subset: Train on a smaller subset of data to speed up training.

Hinge Loss

| Condition | Cost Function | Description |

|---|---|---|

| $y_i \neq \text{sign}(\hat{y}_i)$ | $C(y_ i, \hat{y}_ i) = |y_ i| + 1$ | Large |

| $y_i = \text{sign}(\hat{y}_i)$ close | $C(y_ i, \hat{y}_ i) = |y_ i| + 1$ | Medium |

| $y_i = \text{sign}(\hat{y}_i)$ away | $C(y_ i, \hat{y}_ i) = 0$ | No cost |

| General Cost Function | $C(y_ i, \hat{y}_ i) = \max(0, 1 - y_ i \cdot \hat{y}_ i)$ | - |

Train a SVM

Training Error

- $ \frac{1}{N} \sum_{i=1}^N C(y_i, \hat{y}_ i)$

- $ = \frac{1}{N} \sum_{i=1}^N \max(0, 1 - y_ i \cdot \hat{y}_ i) $

- $ = \frac{1}{N} \sum_{i=1}^N \max(0, 1 - y_i \cdot (\mathbf{w}^T \mathbf{x}_i + b)) $

Cost Function

$$ S(\mathbf{w}, b; \lambda) = \frac{1}{N} \sum_{i=1}^N [\max(0, 1 - y_i \cdot (\mathbf{w}^T \mathbf{x}_i + b))] + \frac{\lambda}{2} \mathbf{w}^T \mathbf{w} $$

Stochastic Gradient Descent

In training a Support Vector Machine (SVM), the primary objective is to minimize the cost function. This cost function often includes terms that measure the classification error and possibly a regularization term. The minimization of the cost function aims to find the best hyperplane that separates the classes while also considering the margin maximization between different classes and controlling model complexity to prevent overfitting.

$$

\mathbf{u} = \begin{bmatrix} \mathbf{w} \ b \end{bmatrix}

$$

Minimize cost function:

$$

g(\mathbf{u}) = \left[ \frac{1}{N} \sum_{i=1}^N g_i(\mathbf{u}) \right] + g_0(\mathbf{u})

$$

where:

$$

g_i(\mathbf{u}) = \max(0, 1 - y_i \cdot (\mathbf{w}^T \mathbf{x}_i + b))

$$

and:

$$

g_0(\mathbf{u}) = \frac{\lambda}{2} \mathbf{w}^T \mathbf{w}

$$

Iteratively, at step $(n)$:

- Compute descent direction $p^{(n)}$ and step size $\eta$

- Ensure that $g(u^{(n)} + \eta p^{(n)}) \leq g(u^{(n)})$

- Update $u^{(n+1)} = u^{(n)} + \eta p^{(n)}$

Descent direction:

$$

p^{(n)} = -\nabla g(\mathbf{u}^{(n)})

$$

$$

= -\left( \frac{1}{N} \sum_{i=1}^N \nabla g_i(\mathbf{u}) + \nabla g_0(\mathbf{u}) \right)

$$

Estimation through mean of batch:

$$

p^{(n)}_ {N_ b} = -\left( \frac{1}{N_b} \sum_ {j \in \text{batch}} \nabla g_ j(\mathbf{u}) + \nabla g_ 0(\mathbf{u}) \right)

$$

Epoch

- One pass on training set of size $N$

- Each step sees a batch of $N_b$ items

- The dataset is covered in $\frac{N}{N_b}$ steps

- Step size in epoch $e$: $\eta^{(e)} = \frac{m}{e + l}$

- Constants $m$ and $l$: tune on small subsets

Season

- Constant number of iterations, much smaller than epochs

- Each step sees a batch of $N_b$ items

- Step size in season $s$: $\eta^{(s)} = \frac{m}{s + l}$

- Constants $m$ and $l$: tune on small subsets

Full SGD

-

Vector u and its gradient:

$$ \mathbf{u} = \begin{bmatrix} u_1 \\ \vdots \\ u_d \end{bmatrix}, \quad \nabla g = \begin{bmatrix} \frac{\partial g}{\partial u_1} \\ \vdots \\ \frac{\partial g}{\partial u_d} \end{bmatrix} $$ -

Batches of 1 sample at each training step:

$$ N_b = 1 $$ -

Gradient of g(u):

$$ \nabla g(\mathbf{u}) = \nabla \left( \max(0, 1 - y_i \cdot (\mathbf{w}^T \mathbf{x}_i + b)) + \frac{\lambda}{2} \mathbf{w}^T \mathbf{w} \right) $$ -

Update rules for a and b:

$$ \begin{bmatrix} \mathbf{w}^{(n+1)} \ b^{(n+1)} \end{bmatrix} = \begin{bmatrix} \mathbf{w}^{(n)} \ b^{(n)} \end{bmatrix} - \eta \begin{bmatrix} \nabla_{\mathbf{w}} \ \nabla_{b} \end{bmatrix} $$ -

Condition for correct classification away from the boundary:

$$ y_ i \cdot (\mathbf{w}^T \mathbf{x}_ i + b) \geq 1. \quad \text{Correct, away from boundary} $$

$$ \nabla_ {\mathbf{w}} (0 + \frac{\lambda}{2} \mathbf{w}^T \mathbf{w}) = \lambda \mathbf{w}, \quad \nabla_ {b}(0 + \frac{\lambda}{2} \mathbf{w}^T \mathbf{w}) = 0 $$ -

Condition for classification close to the boundary or incorrect:

$$ y_ i \cdot (\mathbf{w}^T \mathbf{x}_ i + b) < 1. \quad \text{Correct, close to boundary, or incorrect} $$

$$ \nabla_ {\mathbf{w}} (1 - y_ i \cdot (\mathbf{w}^T \mathbf{x}_ i + b) + \frac{\lambda}{2} \mathbf{w}^T \mathbf{w}) = -y_i \mathbf{x}_ i + \lambda \mathbf{w} $$

$$ \nabla_ {b} (1 - y_ i \cdot (\mathbf{w}^T \mathbf{x}_ i + b) + \frac{\lambda}{2} \mathbf{w}^T \mathbf{w}) = -y_i $$

Stops

Stop when

- predefined number of seasons or epochs

- error on held-out data items is smaller than some threshold

- other criteria

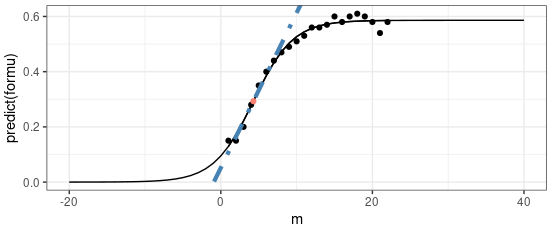

Regularization Constant $ \lambda $

-

Regularization constant $ \lambda $ in $ g(\mathbf{u}) = \frac{1}{2} \lambda \mathbf{w}^T \mathbf{w} $. Try at different scales (e.g., $ \lambda \in {10^{-4}, 10^{-3}, 10^{-2}, 10^{-1}, 1} $)

-

Procedure for Cross-Validation:

- Split dataset into Test Set and Train Set for cross-validation.

- For each $ \lambda_i $ in set to try, iteratively:

- Generate a new Fold from Train Set with a Cross-Validation Train Set and Validation Set.

- Using testing $ \lambda_i $, apply Stochastic Gradient Descent (SGD) on Cross-Validation Train Set to find $ \mathbf{w} $ and $ b $.

- Evaluate $ \mathbf{w} $, $ b $, $ \lambda_i $ on Validation Set and record error for current Fold.

- Cross-validation error for chosen $ \lambda_i $ is average error over all the Folds.

- Using $ \lambda $ with the lowest cross-validation error, apply SGD on whole training set to get final $ \mathbf{w} $ and $ b $.

Support Vector Machine

https://karobben.github.io/2024/09/29/AI/supportvectormachine/