Protein Dock Overview

Physical Based Docking

1982: Dock; Kuntz, Irwin D., et al.[1] (Rigid body-shape based)

|

|---|

| © Kuntz, Irwin D., et al. 1982[1:1] |

In this paper, Kuntz present a way of docking prediction by searching the steric overlap based on the knowing surface structure of 2 proteins. It originally developed by Irwin “Tack” Kuntz and colleagues at the University of California, San Francisco (UCSF), DOCK was initially used for small-molecule docking. However, it laid the foundation for the development of more advanced docking algorithms and software that could handle macromolecular docking.

In the first generation of the Dock, it focus on 2 rigid bodies. It treat 2 proteins as one object. The goal of this program is to fix the 6 degree of freedom (3 transitions and 3 orientations) that determine the best relative position. For achieving this goal, three rules are followed:

- No overlap between 2 proteins

- all hydrogen are pared with N or O within 3.5 Å.

- all ligand atoms within the receptor binding cite.

Dock families:

- 1994: Firstly extend the DOCK into DNA-protein Docking and by screening the Cambridge Crystallographic Database, they find that the protein CC-1065 has high score.[2]

- 1999: DREAM++[3]: It is a extent package for Dock. It use Dock to predict binding and evaluated the interaction and predicts the product, finally search to find the prohibits.

- 2001: DOCK 4.0[4]: It added incremental construction (to sample the internal degrees of freedom of the ligand) and random search. In the Dock4, the ligand is not rigid anymore. Ligands with rotatable-bonds generated multiple conformation by other model.

- 2006: DOCK 5.0[5]:

- anchoring: new scoring functions, sampling methods and analysis tools; energy minimizing was mentioned during the.

- scoring: energy scoring function based on the AMBERL: only intermolecular van der Waals (VDW) and electrostatic components in the function.

- main limitation: Ligands has lots of rotatable-bonds would cause lots of resource. During the test set, ligands with > 7 rotatable bonds were removed.

- Some test data correction: using “Compute” and “Biopolymer” from Sybyl[6] to calculate the Gasteiger–Hückel partial electrostatic charges and add hydrogen for residues.

- 2009: DOCK 6[7]: In this version, it extents it’s abilities in RNA-ligands. But the rotatable-bonds from the ligands are still limited into 7~13. With the increasing of the RNA, the accuracy are decreased.

- update scoring in solvation energy:

- Hawkins–Cramer–Truhlar (HCT) generalized Born with solvent-accessible surface area (GB/SA) solvation scoring with optional salt screening

- Poisson–Boltzmann with solvent-accessible surface area (PB/SA) solvation scoring

- AMBER molecular mechanics with GB/SA solvation scoring and optional receptor flexibility

- other scoring:

- VDW: grid-based form of the Lennard-Jones potential

- electrostatic: Zap Tool Kit from OpenEye

- update scoring in solvation energy:

- 2013: DOCK3.7[8]:

| DOCK4 | DOCK5 | DOCK6 |

|---|---|---|

|

|

|

| incremental: anchor-and-grow | The number of rotatable-bonds hashuge effects on success rate |

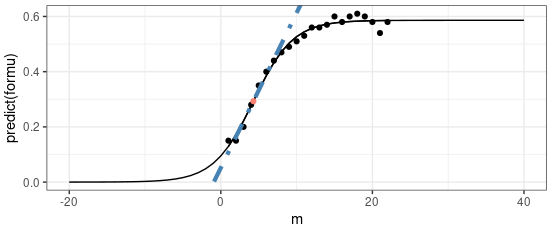

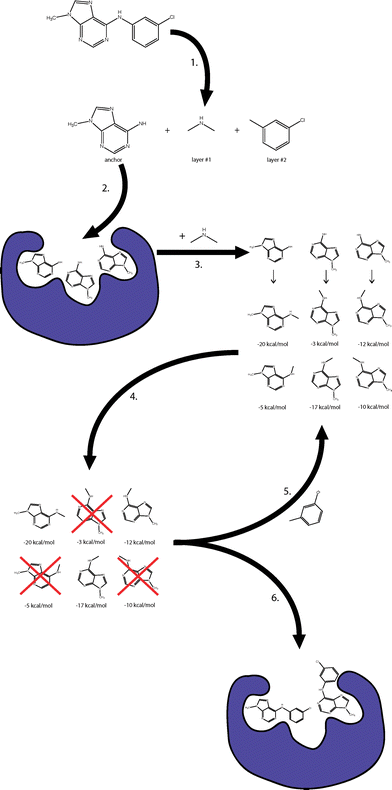

anchor-and-grow

The “anchor-and-grow” conformational search algorithm. The algorithm performs the following steps: (1) DOCK perceives the molecule’s rotatable bonds, which it uses to identify an anchor segment and overlapping rigid layer segments. (2) Rigid docking is used to generate multiple poses of the anchor within the receptor. (3) The first layer atoms are added to each anchor pose, and multiple conformations of the layer 1 atoms are generated. An energy score within the context of the receptor is computed for each conformation. (4) The partially grown conformations are ranked by their score and are spatially clustered. The least energetically favorable and spatially diverse conformations are discarded. (5) The next rigid layer is added to each remaining conformation, generating a new set of conformations. (6) Once all layers have been added, the set of completely grown conformations and orientations is returned

Compare to Other Related Tools

Method | Ligand sampling methoda | Receptor sampling methoda | Scoring functionb | Solvation scoringc,d |

|---|---|---|---|---|

DOCK 4/5 | IC | SE | MM | DDD, GB, PB |

FlexX/FlexE | IC | SE | ED | NA |

Glide | CE + MC | TS | MM + ED | DS |

GOLD | GA | GA | MM + ED | NA |

2003: ZDock

Version iteration:

- ZDOCK 2.3/2.3.2 Scoring Function: Chen R, Li L, Weng Z. (2003) ZDOCK[9]

- ZDOCK 3.0/3.0.2 Scoring Function: Mintseris J, Pierce B, Wiehe K, Anderson R, Chen R, Weng Z. (2007)[10]

- M-ZDOCK: Pierce B, Tong W, Weng Z. (2005) M-ZDOCK[11]

- ZDOCK 3.0.2/2.3.2: Pierce BG, Hourai Y, Weng Z. (2011)[12]

- Online Server: Pierce BG, Wiehe K, Hwang H, Kim BH, Vreven T, Weng Z. (2014) ZDOCK Server[13]

Abstract

ZDock was developed for ubbound docking. It is based on pairwise shape complementarity (Docking) with desolvation and electrostatics (Scoring). In there test, it shows high success rate in the antibody-antigen docking test case. It is especially helpful in “large concave binding pocket”.

Before the ZDock, there are:

- FTDOck: gird-based shape complementarity (GSC) and electrostatic using a Fast Fourier Transform (FFT)

- DOT: FFT-based computes Poission-Bolzmann electrostatics.

- HEX: evaluates overlapping surface skins and electrostatic complementarity with Fourier coorelation.

- GRAMM: low-resolutoin docking with the similar scoring as FTDOck;

- PPD: matches critial poitns by using geometric hashing.

- GIGGER: maximal surface mapping and favorable amino acid contacts by bit-mapping.

- DARWIN: molecular mechanics energy defined according to CHARMM.

For ZDock:

- Optimizes desolvation (GSC), key scoring function.

- GSC = grid points surrounding the receptor corresponding to ligand atoms - clash penalty

- *FFT for electrostatics

- Novel pairwise shape complementarity function (PSC) by distance cut-off of receptor-ligand atom minus clash penalty.

- Favorable: Number of pair within cutoff

- Penalty: The clash penalty for core-core, surface-core, and surface-surface (99, 93, 9)

- DE: desolvation, estimated by atomic contact energy (ACE), which is a free energy change of breaking two protein atom-water contacts and forming a protein atom-protein atom contact and water-water contact. The sum of ACE is DE

Version for scoring functions:

2003: HADDOCK

HADDOCK (High Ambiguity Driven biomolecular DOCKing)[16] is a major information-driven docking suite developed by the Bonvin lab. Unlike purely geometry/energy-based tools (e.g. ZDock), HADDOCK is designed to use experimental or predicted information about the interface to guide docking, which often yields more biologically relevant poses when such data exist.

| Aspect | Description |

|---|---|

| Philosophy | Integrate biochemical/biophysical data (NMR, mutagenesis, cross-linking, evolutionary contacts, etc.) as Ambiguous Interaction Restraints (AIRs) instead of relying only on shape/electrostatics. |

| AIRs | Active residues: those known or predicted to be at the interface (solvent-accessible). Passive residues: surface neighbors of active residues. AIRs drive the partners toward plausible binding modes without over-constraining exact contacts. |

| Workflow | Typically (i) rigid-body docking (e.g. FFT-based sampling), (ii) semi-flexible refinement (flexible interface), (iii) optional explicit solvent refinement. |

| Use cases | Antibody–antigen, protein–protein, protein–nucleic acid; especially when you have interface hints (e.g. critical residues, cross-links, or bioinformatics predictions). |

HADDOCK is widely used in structural biology and is available as a web server and for local runs (HADDOCK2.4, HADDOCK3). It complements ab initio methods like ZDock when interface information is available.

2004: ClusPro

ClusPro: a fully automated algorithm for protein–protein docking

2010: Hex

Ultra-fast FFT protein docking on graphics processors

Hex is extremely fast but lack of accuracy. I tried to sampling over 100,1000 but results even close to native structure.

On the other hand, I didn’t find a way to mark the surface residues so we could focus on specific area. Although, GhatGPT said it could do constrained docking, but it seems we could only constrain the range angles of the receptor and the ligand.

|

|---|

| © SAMSON |

2014: rDock

rDock: a fast, versatile and open source program for docking ligands to proteins and nucleic acids

2018: InterEvDock

Protein-Protein Docking Using Evolutionary Information

Machine Learning Based Docking

2021: DeepRank

| Model Grpah Abstract | Model Name |

|---|---|

© Chen, M., & Zhou, X |

DeepRank |

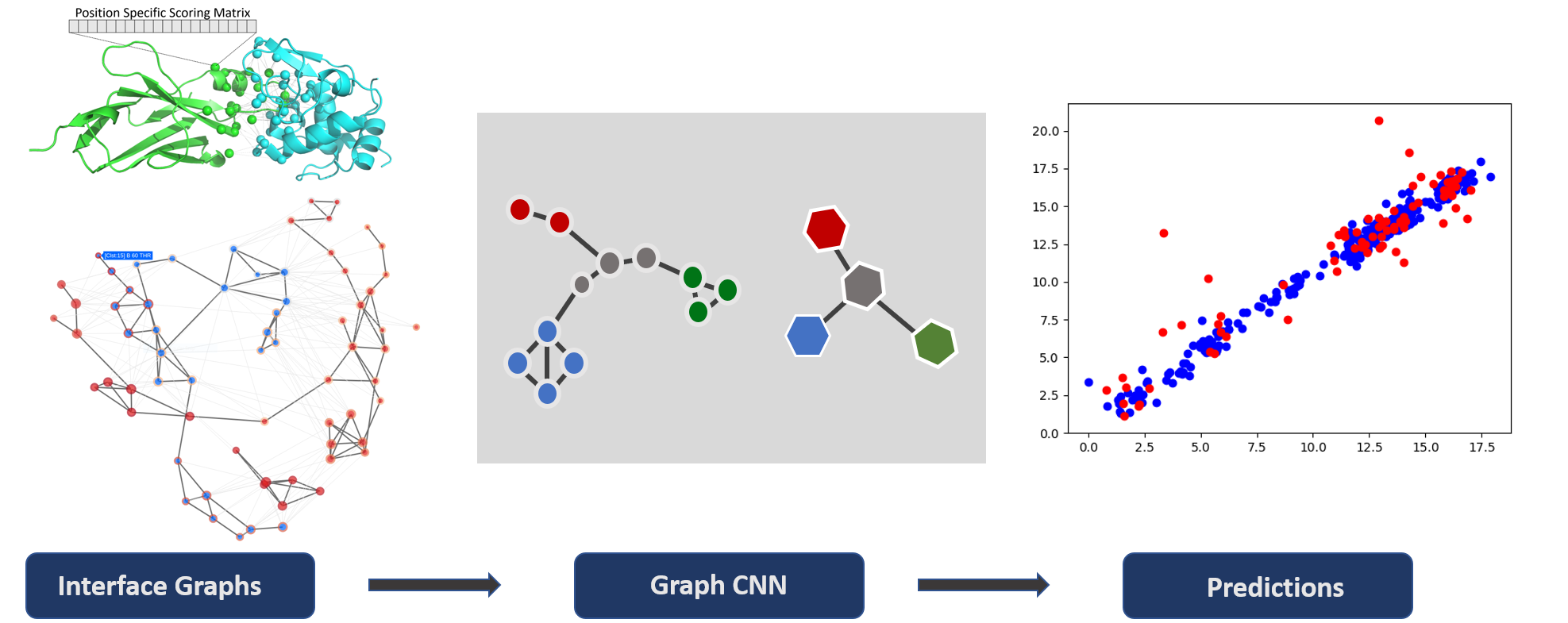

© Réau, M. |

DeepRank-GNN |

© Crocioni, G. |

Deeprank2 |

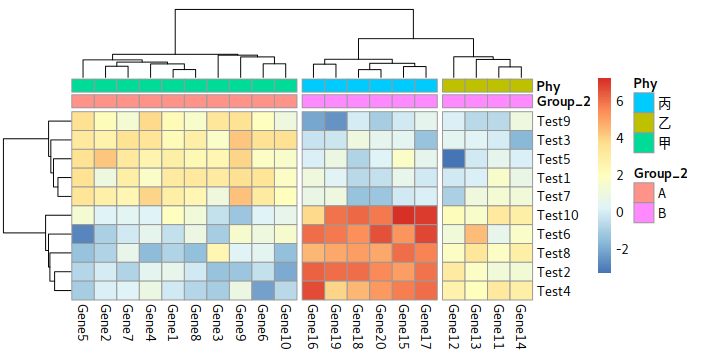

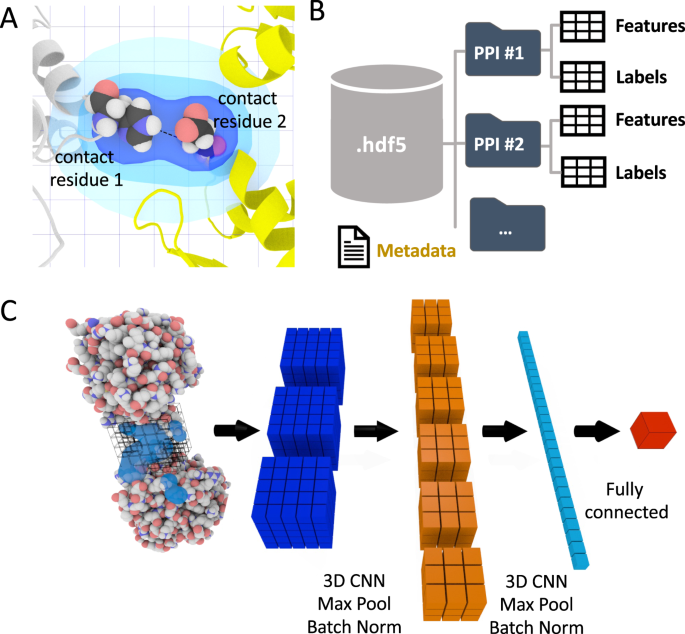

DeepRank[17] is a open source framework designed to analyze 3D protein-protein interfaces by using deep learning to capture spatial and biochemical features. The paper presents DeepRank’s approach to transforming 3D structural data into 3D grids that a neural network can process. This setup allows DeepRank to identify interaction patterns, rank docking models, and predict binding affinities with high accuracy. It’s especially useful for discovering patterns in protein interfaces that might be overlooked with traditional scoring functions.

In this model, it turn the pdb into sql for efficient processing. The interfacing residues cut-off is 5.5 Å. When find all interfacing atoms, they would be mapped into **3D grid using a Gaussian mapping. The target value is very flexible, too. You can using any kind of values, iRMSD, FNAT, or DockQ score for instance, as the target values (Predicted value). The data was stored as hdf5 format which keep the efficiency and small storage size.

DeepRank family:

- DeepRank[17:1]: 2021, Chen, M., et al.; It mapped the protein interfacing into a 3D grid and using CNN to train the regression model. It established the foundation of the architectural of DeepRank.

- In the DeepRank, it use information both from atom-level and residue-level. From the atom level, it calculates the atom density, charges, electrostatic energy, and VDW contacts. In residue-level, it included number of residue-residue contacts, buried surface area, and Position specific scoring matrix (PSSM)

- DeepRank-GNN[18]: 2023, Réau, M. et al.; from the same team replace the 3D grid based CNN into GNN which could avoid rotation challenge in 3D grid.

- The input information is very similar to the DeepRank. Instead of 3D grid, it relies on the adjacent matrix to build the network. In this time, the cut-off became 8.5 Å.

- It has more rich features like Distance, residue half sphere exposure, Residue depth (from biopython, MSMS)

- Deeprank_GNN_ESM[19]: 2024, Xu, X., et al.; The PSSM calculating requires sequence alignment which consumes lots of time. For generate the graph efficiently, they replaced the PSSM with ESM embedding vectors.

- DeepRank2[20]: 2024, Crocioni, G., et al.; In the DeepRank2., it supports both 3D grid and graph network as inputs. It also integrated the Deep-Mut to do in silicon mutation screening.

DockQ

- DockQ: a quality measure for protein–protein docking models

- DockQ v2: improved automatic quality measure for protein multimers, nucleic acids, and small molecules

DockQ is a knowledge based docking evaluation tool. It divided the docking results into 4 categories: Incorrect, Acceptable, Medium, or High quality. The score it uses is: Fnat, LRMS, and iRMS as proposed and standardized by CAPRI. The training set are extremely in balanced. It has over 56,000 incorrect docking, 760 acceptable, 850 mdeium, and 74 high quality. w

Online Tools

- ClusPro AbEMap: The ClusPro AbEMap web server for the prediction of antibody epitopes

- ClusterPro?

- CCharPPI

- AbAgIntPre: No structure, binary output results only

- CSM-AB: CSM-AB: graph-based antibody–antigen binding affinity prediction and docking scoring function

Other tools

- [ZRANK2]

Other Infor

Kuntz I D, Blaney J M, Oatley S J, et al. A geometric approach to macromolecule-ligand interactions[J]. Journal of molecular biology, 1982, 161(2): 269-288. ↩︎ ↩︎

Grootenhuis P D J, Roe D C, Kollman P A, et al. Finding potential DNA-binding compounds by using molecular shape[J]. Journal of Computer-Aided Molecular Design, 1994, 8: 731-750. ↩︎

Makino S, Ewing T J A, Kuntz I D. DREAM++: flexible docking program for virtual combinatorial libraries[J]. Journal of computer-aided molecular design, 1999, 13: 513-532. ↩︎

Ewing T J A, Makino S, Skillman A G, et al. DOCK 4.0: search strategies for automated molecular docking of flexible molecule databases[J]. Journal of computer-aided molecular design, 2001, 15: 411-428. ↩︎

Moustakas D T, Lang P T, Pegg S, et al. Development and validation of a modular, extensible docking program: DOCK 5[J]. Journal of computer-aided molecular design, 2006, 20: 601-619. ↩︎

S. Pérez, C. Meyer, A. Imberty. “Practical tools for accurate modeling of complex carbohydrates and their interactions with proteins” A. Pullman, J. Jortner, B. Pullman (Eds.), Modelling of Biomolecular Structures and Mechanisms, Kluwer Academic Publishers, Dordrecht (1996), pp. 425-454. ↩︎

Lang P T, Brozell S R, Mukherjee S, et al. DOCK 6: Combining techniques to model RNA–small molecule complexes[J]. Rna, 2009, 15(6): 1219-1230. ↩︎

Coleman R G, Carchia M, Sterling T, et al. Ligand pose and orientational sampling in molecular docking[J]. PloS one, 2013, 8(10): e75992. ↩︎

Chen, R., Li, L., & Weng, Z. (2003). ZDOCK: an initial‐stage protein‐docking algorithm. Proteins: Structure, Function, and Bioinformatics, 52(1), 80-87. ↩︎ ↩︎ ↩︎

Mintseris, J., Pierce, B., Wiehe, K., Anderson, R., Chen, R., & Weng, Z. (2007). Integrating statistical pair potentials into protein complex prediction. Proteins: Structure, Function, and Bioinformatics, 69(3), 511-520. ↩︎

Pierce, B., Tong, W., & Weng, Z. (2005). M-ZDOCK: a grid-based approach for C n symmetric multimer docking. Bioinformatics, 21(8), 1472-1478. ↩︎

Pierce, B. G., Hourai, Y., & Weng, Z. (2011). Accelerating protein docking in ZDOCK using an advanced 3D convolution library. PloS one, 6(9), e24657. ↩︎

Pierce, B. G., Wiehe, K., Hwang, H., Kim, B. H., Vreven, T., & Weng, Z. (2014). ZDOCK server: interactive docking prediction of protein–protein complexes and symmetric multimers. Bioinformatics, 30(12), 1771-1773. ↩︎

Chen R, Weng Z. Docking unbound proteins using shape complementarity, desolvation, and electrostatics. Proteins 2002; 47: 281–294. ↩︎

Chen R, Weng Z. A novel shape complementarity scoring function for protein-protein docking. Proteins 2003; 51: 397–408. ↩︎

Dominguez C, Boelens R, Bonvin AM. HADDOCK: a protein–protein docking approach based on biochemical and/or biophysical information. J Am Chem Soc. 2003;125(7):1731-1737. ↩︎

Renaud, N., Geng, C., Georgievska, S., Ambrosetti, F., Ridder, L., Marzella, D. F., … & Xue, L. C. (2021). DeepRank: a deep learning framework for data mining 3D protein-protein interfaces. Nature communications, 12(1), 7068. ↩︎ ↩︎

Réau, M., Renaud, N., Xue, L. C., & Bonvin, A. M. (2023). DeepRank-GNN: a graph neural network framework to learn patterns in protein–protein interfaces. Bioinformatics, 39(1), btac759. ↩︎

Xu, X., & Bonvin, A. M. (2024). DeepRank-GNN-esm: a graph neural network for scoring protein–protein models using protein language model. Bioinformatics advances, 4(1), vbad191. ↩︎

Crocioni, G., Bodor, D. L., Baakman, C., Parizi, F. M., Rademaker, D. T., Ramakrishnan, G., … & Xue, L. C. (2024). DeepRank2: Mining 3D Protein Structures with Geometric Deep Learning. Journal of Open Source Software, 9(94), 5983. ↩︎

Protein Dock Overview