Fly Behaviors: Oder and Forage

Behaviors

Courtship

Foraging

The short neuropeptide F receptor regulates olfaction-mediated foraging behavior in the oriental fruit fly Bactrocera dorsalis (Hendel)

|

|---|

| © Hong-Fei Li, et al |

Abstract

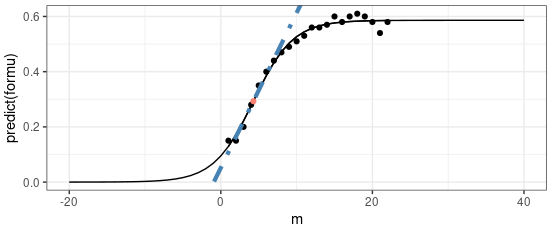

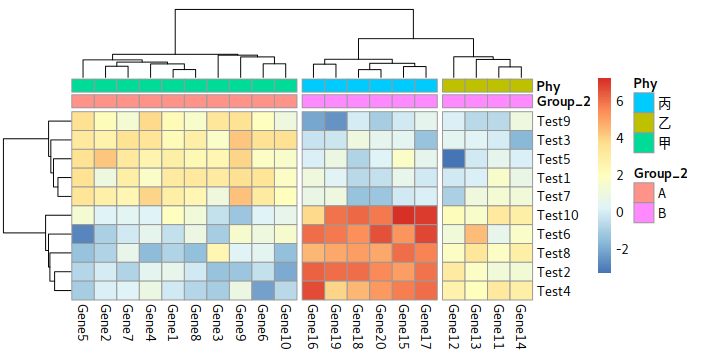

- The short neuropeptide F (sNPF) signaling system, consisting of sNPF and its receptor (sNPFR), influences many physiological processes in insects, including feeding, growth and olfactory memory.

- sNPF regulates olfactory sensitivity in the oriental fruit fly Bactrocera dorsalis (Hendel) during starvation

Behavior assay

Flies were transferred to a clean mesh cage (40 cm × 40 cm × 40 cm) for acclimatization and starvation 1 day before the experiment. On the day of the experiment, flies (sex ratio 1:1) were transferred individually to a clean chamber (10 cm × 10 cm × 12 cm) and allowed to acclimatize for 20 min. Then, 10 μL of artificial food, or 0.5 g fully ripe orange, or 0.5 g fully ripe banana (Jayanthi et al., 2012; Rattanapun et al., 2009; Zhu et al., 2018) was placed in the center of the chamber. Foraging behavior was observed for 15 min. Latency was defined as the time elapsed before the fly landed on the food. All foraging behavior assays took place between 16:00 and 18:00.

Elementary sensory-motor transformations underlying olfactory navigation in walking fruit-flies

cite: Álvarez-Salvado, Efrén, et al. “Elementary sensory-motor transformations underlying olfactory navigation in walking fruit-flies.” Elife 7 (2018): e37815.

|

|---|

| © Efrén Álvarez-Salvado, et al |

Abstract

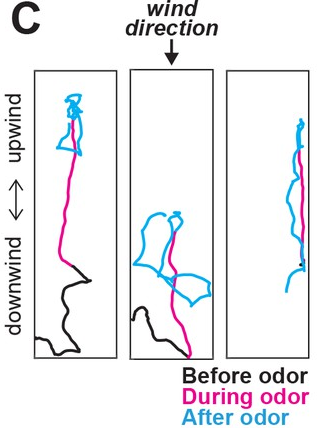

Odor attraction in walking Drosophila melanogaster is commonly used to relate neural function to behavior, but the algorithms underlying attraction are unclear. Here, we develop a high-throughput assay to measure olfactory behavior in response to well-controlled sensory stimuli. We show that odor evokes two behaviors: an upwind run during odor (ON response), and a local search at odor offset (OFF response). Wind orientation requires antennal mechanoreceptors, but search is driven solely by odor. Using dynamic odor stimuli, we measure the dependence of these two behaviors on odor intensity and history. Based on these data, we develop a navigation model that recapitulates the behavior of flies in our apparatus, and generates realistic trajectories when run in a turbulent boundary layer plume. The ability to parse olfactory navigation into quantifiable elementary sensori-motor transformations provides a foundation for dissecting neural circuits that govern olfactory behavior.

Aggressive Behavior

Fighting fruit flies: A model system for the study of aggression

Cite:

| |

|

|:-:|Despite the importance of aggression in the behavioral repertoire of most animals, relatively little is known of its proximate causation and control. To take advantage of modern methods of genetic analysis for studying this complex behavior, we have developed a quantitative framework for studying aggression in common laboratory strains of the fruit fly, Drosophila melanogaster. In the present study we analyze 73 experiments in which socially naive male fruit flies interacted in more than 2,000 individual agonistic interactions. This allows us to (i) generate an ethogram of the behaviors that occur during agonistic interactions; (ii) calculate descriptive statistics for these behaviors; and (iii) identify their temporal patterns by using sequence analysis. Thirty-minute paired trials between flies contained an average of 27 individual agonistic interactions, lasting a mean of 11 seconds and featuring a variety of intensity levels. Only few fights progressed to the highest intensity levels (boxing and tussling). A sequential analysis demonstrated the existence of recurrent patterns in behaviors with some similarity to those seen during courtship. Based on the patterns characterized in the present report, a detailed examination of aggressive behavior by using mutant strains and other techniques of genetic analysis becomes possible.

|© Selby Chen, et all|

AB

Despite the importance of aggression in the behavioral repertoire of most animals, relatively little is known of its proximate causation and control. To take advantage of modern methods of genetic analysis for studying this complex behavior, we have developed a quantitative framework for studying aggression in common laboratory strains of the fruit fly, Drosophila melanogaster. In the present study we analyze 73 experiments in which socially naive male fruit flies interacted in more than 2,000 individual agonistic interactions. This allows us to (i) generate an ethogram of the behaviors that occur during agonistic interactions; (ii) calculate descriptive statistics for these behaviors; and (iii) identify their temporal patterns by using sequence analysis. Thirty-minute paired trials between flies contained an average of 27 individual agonistic interactions, lasting a mean of 11 seconds and featuring a variety of intensity levels. Only few fights progressed to the highest intensity levels (boxing and tussling). A sequential analysis demonstrated the existence of recurrent patterns in behaviors with some similarity to those seen during courtship. Based on the patterns characterized in the present report, a detailed examination of aggressive behavior by using mutant strains and other techniques of genetic analysis becomes possible.

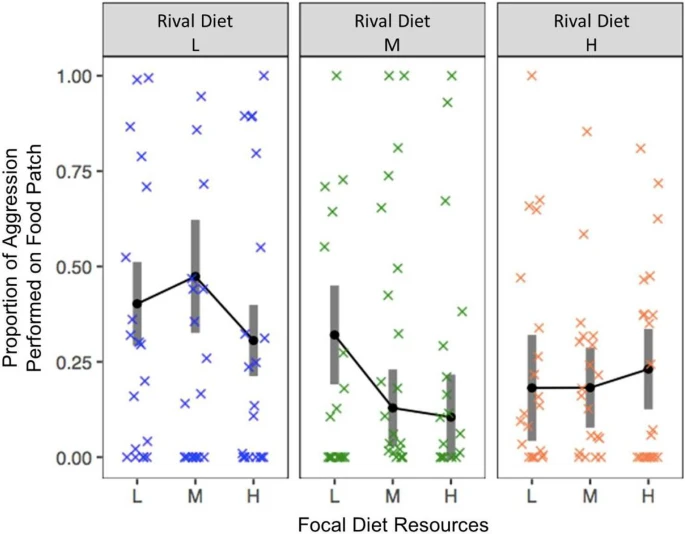

A resource-poor developmental diet reduces adult aggression in male Drosophila melanogaster

|

|---|

| © Danielle Edmunds, et al |

Abstract

- resource-poor developmental nutrition might decrease adult aggression by limiting growth and energy budgets, or alternatively might increase adult aggression by enhancing motivation to compete for resources

- low-resource developmental diet reduced the probability of aggressive lunges in adults, as well as threat displays against rivals

- independent of diet-related differences in body mass

- Low-resource die: facing rivals → Males aggression↑

- social effects

Behavioural trials

- Pre-treatment

- 2 h: food-deprived in moist cotton wool

- Transfer to chamber: 20-mm diameter, 5-mm depth containing a food patch (5-mm diameter)

- In each pair, we arbitrarily designated one male as the focal male and the other as the rival male

- 20–21 pairs per combination

- 5-min acclimatisation period, 15 min recording

- scored the videos using JWatcher

- five aggressive behaviours (fencing, chasing, tussling, lunging and wing threat)

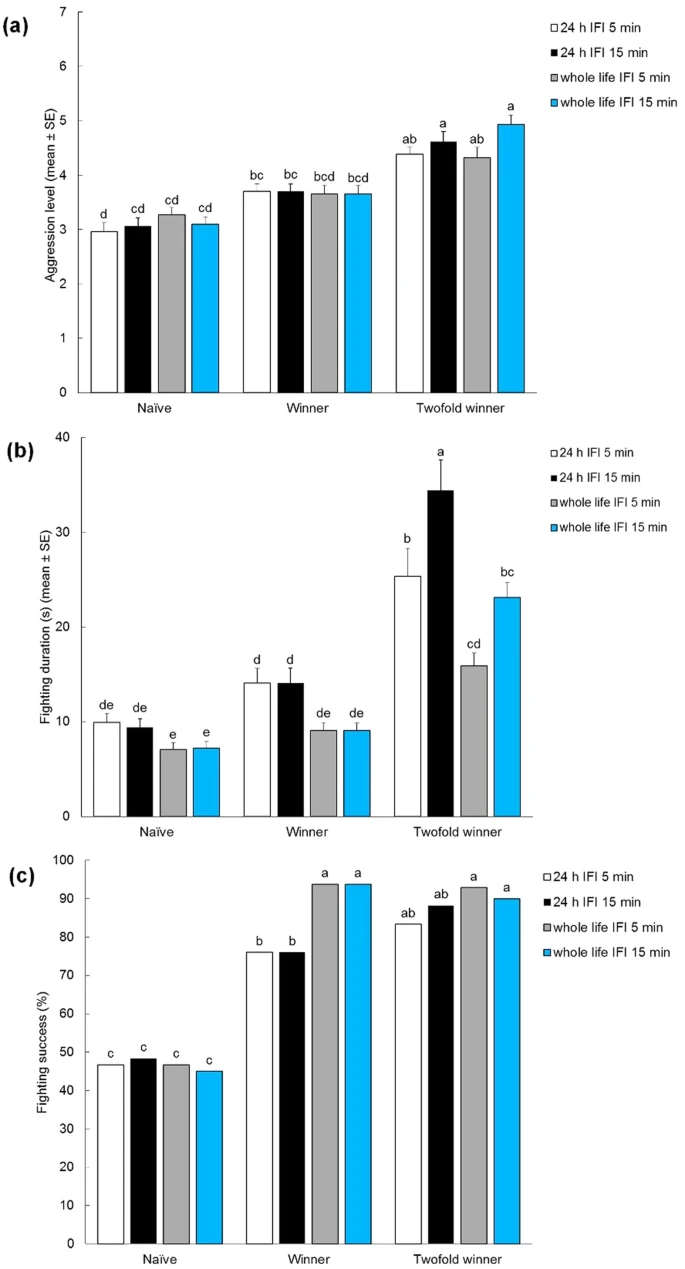

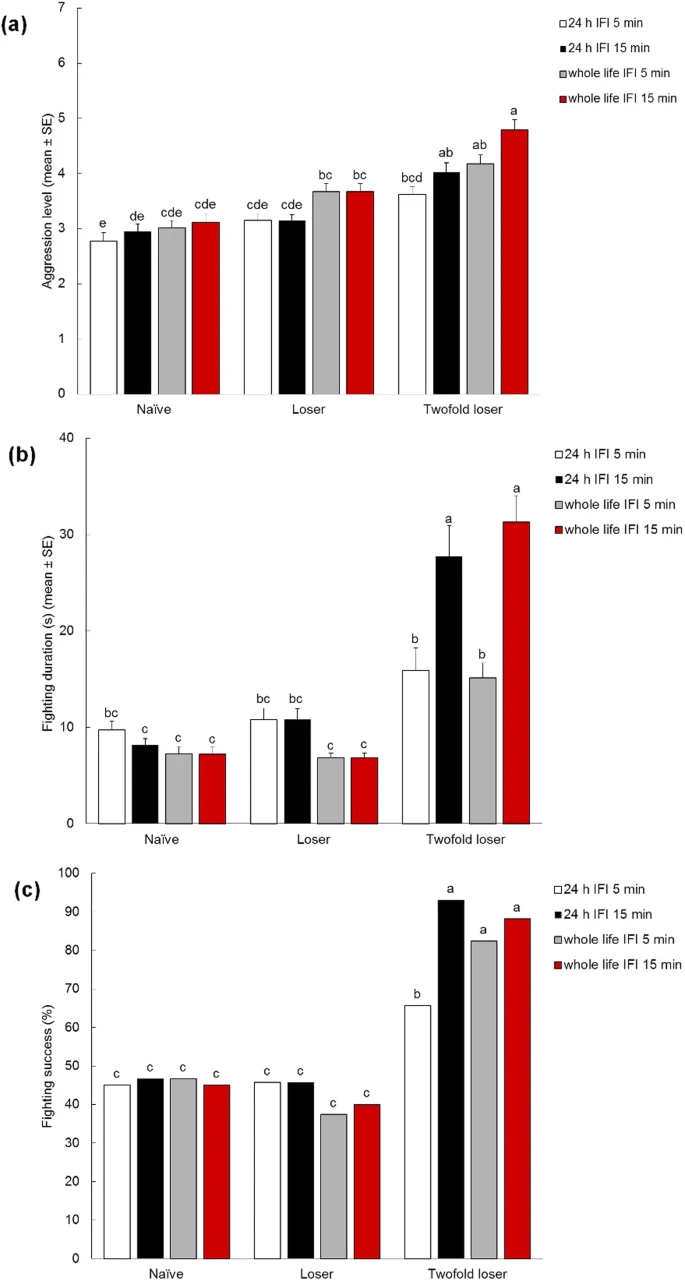

Contest experience enhances aggressive behaviour in a fly: when losers learn to win

|

|

|---|---|

| © Giovanni Benelli, et al |

Abstract

previous victories and defeats both enhance aggressive behaviour in olive fruit flies, allowing them to achieve higher fighting success in subsequent contests against inexperienced males.

Fly Behaviors: Oder and Forage

https://karobben.github.io/2021/09/25/LearnNotes/fly-behavior/